Reporting on his visit to Ann Arbor as a ScienceCampus fellow, UR historian Timothy Nunan reflects on the making of our historical epoch. He focuses on events around 1979 in Iran, Afghanistan and the Middle East. As well as outlining his ongoing research on how Shi’a Islamist actors challenged the bipolar world of the Cold War in the 1970s and 1980s, he considers the value of the specialist library collections in Michigan and exchanges with experts, while also offering insight into what you can do during some downtime in Ann Arbor.

© IMAGO / Pond5 Images

Generate PDF

When did our world come into being? What divides one historical epoch from another? Such questions of periodization preoccupy historians, who often speak of a “long 19th century (1789–1914) or a “short 20th century” (1914-1989). In using such metaphors, historians recognize that historical change is not always constant. Rather, historical time is often punctuated by Zeitenwenden – shocks like the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Covid-19 pandemic that shut down the world economy from February 2020, or the twin shocks of Brexit and Trump in 2020. Making sense of such turning points, and the ways in which they open or close historical eras, belongs to the heart of historians’ work.

doi number

10.15457/frictions/0027

historians recognize that historical change is not always constant. Rather, historical time is often punctuated by Zeitenwenden – shocks like the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Covid-19 pandemic that shut down the world economy from February 2020, or the twin shocks of Brexit and Trump in 2020

Future historians are likely to debate the events of 2020-2023 as decisive turning points leading into a new era. Yet if that’s the case, when did the era that these events closed start? In recent years, historians have come to see the 1970s, and the year 1979 in particular, as decisive for the making of the era that followed. The 1970s saw oil shocks that upended the world economy and led, in Germany, to severe restrictions on migration. The women’s liberation movement questioned gender norms. China’s re-emergence into the world following the Cultural Revolution transformed world geopolitics. In February 1979, the Shah’s regime in Iran was toppled and replaced by a Shi’a theocracy. In December of that same year, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan.

My research explores the myriad ways in which the events of 1979 came to shape our world today. My first book explored the history of Soviet developmental aid to Afghanistan during the Cold War, while my ongoing research examines how Shi’a Islamist actors challenged the bipolar world of the Cold War in the 1970s and 1980s. The sources we need to write such histories are, however, spread far and wide. Travel to Russia, Afghanistan, or Iran remains challenging for Western researchers.

So, in September 2023 I had the privilege of spending a month as a Visiting Scholar at the Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia at the University of Michigan, thanks to the support of the Leibniz ScienceCampus “Europe and America in the Modern World.” Ann Arbor—the city home to the University of Michigan—was an obvious destination, and not only because of its status as a partner institution of UR. UMich has a rich tradition of studying Russia and Eurasia from the point of view of the Caucasian and Central Asian borderlands. And while Germany inter-library loan networks offer scholars like me invaluable resources, major American university libraries like Hatcher Graduate Library simply have more resources than even the best German libraries. The month in Michigan was thus a rich one, full of exchanges with colleagues on works in progress and much time spent in the stacks, gathering sources for current and future research.

Exchanges with Michigan Faculty and students — and a visit to “The Big House”

My visit to Ann Arbor was punctuated by two events that gave me an opportunity to share my research with Michigan faculty and students. Shortly after arriving, I had the opportunity of presenting a chapter from my current book project on the Soviet Union and Iran’s stances toward Afghanistan in the 1980s at the UMich “kruzhok” (“little circle”) for Russian and Eurasian History. Iranian Islamist actors had longstanding ties with their Afghan counterparts, but following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, they were forced to rethink how to “export” the revolution to their eastern neighbor. My book chapter showed how Iranian and Afghan Shi’a Islamists introduced tactics of armed struggle into their ideological program as they pushed back against the Soviet Army. At the colloquium, graciously hosted by Professor Jeffrey Veidlinger, I had the chance to engage in a give and take with Michigan professors like Ron Suny and Douglas Northrop, as well as graduate students working on Central Asian history.

If the kruzhok was a specialist conversation among fellow historians, later in September I had the opportunity to present (snippets of) my research to a wider audience at the Weiser Center. On September 13, 2023, I delivered the Noon Lecture for the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies (one of Michigan’s many area studies centers), titled: “‘Imam of Atheism’ to ‘Orthodox Iran’: Russia and Shi’a Islamist Movements, 1970s-Present.” In the talk (which was recorded and is available on YouTube) I explore the longer-term history of ties between Russia and Shi’a Islamist movements. As I show, while Shi’a Islamist groups originally emerged as anti-Communist actors, the most successful such movement—the Iranian one—came to adopt a more pragmatic stance toward the Soviet Union during the twilight of the Cold War. The lecture combines materials from my current book research with reflections on more recent developments in Russian-Iranian relations. Questions from the audience pushed me to dwell more on how (or if) Islamophobia(s) travel within Eastern Europe, as well as the special role of Armenia as a bridge between Russia and Iran.

The University of Michigan Wolverines take on the University of Nevada, Las Vegas Rebels at Michigan Stadium on September 9, 2023. The second-ranked Michigan team easily dispatched the Rebels 35-7.

Amid these conversations and lectures, however, I made sure to take time to engage with Michigan’s campus culture in a very different way — namely, by attending a football game at “the Big House,” Michigan’s enormous football stadium. The Wolverines are among the top teams in the country this year, and on Saturday game days, tens of thousands of fans come to Ann Arbor to tailgate around Michigan Stadium (the third-largest in the world). While Michigan’s football coach, Jim Harbaugh, was absent for the game (due to a larger string of scandals concerning recruiting; see also), Michigan easily dispatched its opponent, the UNLV Rebels. Even for a college football fan such as the author, attending a game at the Big House (including spectacles such as parachute jumpers, the marching band, and a frisbee-catching dog) was a welcome break from colloquia and lectures.

Lost in the stacks

Beyond my exchanges with scholars and students in Ann Arbor (and following the Wolverines), another highlight of the time in Michigan was simply exploring the rich holdings of Hatcher Graduate Library. Like many large American research libraries, Michigan (still) boasts subject librarians who actively purchase books in regional languages and from countries like Iran or Syria. Developing such collections over time means that the best university libraries may have a rich selection of secondary literature and primary sources, like memoirs, from these countries that are hard to find elsewhere.

Michigan’s holdings for the countries that I study, like Russia, Iran and Afghanistan did not disappoint in this regard. I spent many hours scouring the bookshelves on the fifth floor of Hatcher Graduate Library to chase down books and references that had eluded me in Germany. One interesting find, for instance, were the memoirs of post-revolutionary Iran’s Foreign Minister, Ali Akbar Velayati. Velayati’s memoirs discussed in detail how the revolutionary regime sought to balance its pretensions to challenge the world order with the realities of regional diplomacy. Among other episodes, for instance, Velayati describes the balancing act of Iranian diplomacy with Syria in the early 1980s. Syria was Tehran’s only significant ally in the Arab World—no small asset during the Iran-Iraq War—but the secular Syrian regime’s massacre of Islamist opposition groups meant that the Iranians faced significant criticism for cozying up to Damascus.

the revolutionary [Iranian] regime sought to balance its pretensions to challenge the world order with the realities of regional diplomacy

This tension between the need for strong state allies and claims to provide an example to other Islamist movements would mark Iranian diplomacy for much of the 1980s, and is a theme in my forthcoming book. As I drafted the conclusion for said book in the Weiser Center, other findings in Hatcher helped me see the outlines of a larger story. One was a 2017 book, Iran From the Inside by the Iraqi Arab intellectuals like one Nabil al-Heydari. Heydari had once supported the Islamic Republic of Iran and lived there as an exile during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s. But writing in the shadow of the Syrian Civil War, Heydari blasted Tehran for its backing of the Assad regime. Heydari admitted that he had been fooled by the Iranians in the 1980s: they were not committed to Islam or anti-imperialism, but rather only to a (in his view) project of anti-Arab Persian imperialism. Here was a larger data point in the story of Iranian-Syrian relations. While books like Velayati’s or Heydari’s exist in libraries outside of Michigan, being able to explore the vast open stacks of Hatcher and follow threads between these works marked an essential contribution to my research.

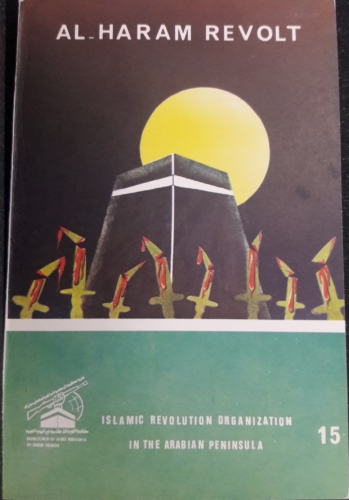

One final highlight of my time in Michigan’s libraries, however, was a trip to Special Collections on one of the top floors of Hatcher Graduate Library. Scouring the Michigan library catalog, I had noticed that the libraries held a rare—in fact, unique in the world—copy of an English-language publication about the Siege of the Grand Mosque of Mecca. For context, recall that in December 1979, Saudi Arabian Islamist groups managed to besiege the main mosque in Mecca, part of a larger plot to bring down the Saudi monarchy. The precise role of any Iranian actors in supporting the action remains unclear, but Tehran and the Islamist groups it did support celebrated the action.

Al-Haram Revolt, a book produced by the Islamic Liberation Organization of the Arabian Peninsula following the siege of the Grand Mosque of Mecca in 1979. The University of Michigan’s Special Collections Library contains of the few—if not the only—extant copy of this book. To the best knowledge of the author, this book is not in copyright.

One of these groups, the Islamic Liberation Organisation of the Arabian Peninsula, was so impressed by the siege of Mecca that it published an entire English-language book in admiration of the Saudis who had challenged the Saudi monarchy. The cover of the book, Al-Haram Revolt, presented the Ka’aba (the stone building at the center of the Grand Mosque in Mecca) surrounded by shattered swords. One way or another, this book—produced in a microscopic print run in revolutionary Tehran—made it to Ann Arbor. Thanks to the support of Hatcher’s librarians, I was able to examine and photograph this book for my research and teaching. Set alongside the many Arabic- and Persian-language publications that groups like the Islamic Liberation Organisation of the Arabian Peninsula produced, this source can help us understand the aspirations of these Islamist actors who sought to upend the world in 1979. Indeed, I hope to use excerpts from the book as I teach a seminar this coming summer semester on the global history of the 1970s.

In sum, the trip to Michigan was a rich opportunity to meet and exchange ideas with fellow scholars and students. It helped me deepen and widen the sources that I use for my research and teaching in Regensburg. And – even for this American professor in Germany – it was a culturally rich dive into the workings (and football victories) of a major American research university. I am grateful to the Leibniz ScienceCampus “Europe and America in the Modern World” for its support.

© 2023. This text is openly licensed via CC BY-NC-ND. Separate copyright details are provided with each image. The images are not subject to a CC licence.