Abstract: Victoria Harms’ essay revisits the foundational mythologies of Johns Hopkins University (JHU) by critically tracing the long history of exclusion, merit, and institutional identity across lines of race, gender, class, and religion. She examines how JHU’s early adoption of the German research university model coexisted with entrenched structures of elitism and systematic exclusion—from barring women and Black students to implementing antisemitic admissions policies. The article foregrounds the tension between JHU’s self-image as a beacon of meritocracy and its historical reality as a gatekeeper of privilege. While the university has taken recent steps to diversify its student body and admissions policies, these reforms remain fragile amid renewed political hostility to inclusion. By interweaving institutional biography with broader social and political transformations, Harms reveals how the legacies of exclusion continue to shape contemporary higher education in the United States, offering a critical, thought-provoking contribution to current debates and legal contestations over DEI, race, gender and antisemitism.

Images by Victoria Harms; the numbers of the images refer to references in the text

Generate PDF

Introduction

For decades after its founding in 1876, Angela Merkel would not have been allowed into its seminars let alone afforded a degree.

During her farewell tour of the United States in July 2021, German Chancellor Angela Merkel received an honorary degree of humane letters from Johns Hopkins University (JHU), one of the world’s top-ranked universities. Johns Hopkins President Ron Daniels eulogized Merkel’s “trademark frankness and integrity” and “singular combination of pragmatism and idealism.” He evoked the perception of Merkel, the trained physicist, as a beacon of stability and rational policies in a world of democratic backsliding and distrust of expertise. Her leadership, he contended, had “ensure[d] that Germany and so many other European nations have remained open, dynamic societies that place a premium on freedom of speech and thought that welcome dissent and heterodoxy.”[1]

The chairman of the university’s board explained that the choice symbolized the “strong and enduring bridges between our university and Germany.”[2] Doubling down on the connection, Daniels added: “Johns Hopkins University took its inspiration from the German university model, borne to a shared commitment to free inquiry, open debate, and the pursuit of truth through rigorous research.” He concluded with a historical nugget that elicited the intended giggles: “We are proud to call ourselves America’s first research university, and we have not forgotten that our nickname used to be ‘Göttingen in Baltimore.’”[3]

The lionization of Merkel set the scene for the celebration of universities as guarantors of liberal democracy and incubators of science and innovation, rational and critical, critical reflection.[4] Meritocracy sits at the root of such conceptualizations of the university as gathering place of the best and brightest who then churn out results and discoveries benefitting society at large. A look into Johns Hopkins’ history, however, offers a somber counter-story. For decades after its founding in 1876, Angela Merkel would not have been allowed into its seminars let alone afforded a degree. The first women were only admitted to the undergraduate program in 1970, when Merkel was sixteen and JHU ninety-four years old. During that time, it had not only systematically excluded women, but also Black Americans, temporarily Jewish students and faculty and students from poor families.

doi number

doi: 10.15457/frictions/0042

Centering the archival evidence of exclusion shows that discrimination might not be an inadvertent flaw… but systemic and reflective of the history of the US at large

Universities in Trouble

Whereas public colleges and universities have been pummeled with austerity policies for over two decades, elite US universities, many of them private, have come under attack in recent years, too.[5] Criticism from the left, broadly speaking, has targeted the dominance of students from wealthy, mostly white families. As prominently outlined in Daniel Golden’s 2006 bombshell The Price of Admission, parents could invest in tutoring and training or donate generously to see their kids through, turning the top schools into secluded training centers for the already privileged.[6] Meanwhile, right-wing media, influencers, the Republican party, and already the Trump administrations have furiously accused universities of leftist indoctrination. “unfair” admission practices, and “racist,” i.e. anti-white, social engineering via DEI policies (diversity, equity, inclusion).

In his 2021 book What Universities Owe Democracy, Ron Daniels admits that the historic exclusivity of first-class education in the US would constitute “a painful truth”: “For too many lower- and middle-income families, the nation’s colleges and universities, which ought to be our greatest emblem of equal opportunity, are seen as the exclusive reserve of privileged and entrenched elites.”[7] He also acknowledged the anger among President Trump’s followers, “many of whom have been on the losing side of globalization’s steady march over the past several decades.”[8] Nevertheless, What Universities Owe Democracy presents a fierce defense of meritocracy and universities as bastions of innovation that engender democracy and social cohesion. As evidence of his integrity, commitment to fairness and ever-lasting progress, he marshals the suspension of legacy admissions, i.e., the preferential treatment of children of alumni, at Johns Hopkins in 2014 – contrary to Harvard and other elite schools who hold on to that practice.[9]

The legitimacy crisis of higher education, compounded by growing skepticism towards science and expertise generally since the Covid-19 pandemic has inspired scholars to seek answers to the country’s problems in the origin stories of places such as Johns Hopkins, pillars of scientific excellence, which propelled the US to a superpower after World War II.[10] Aside from Daniels, others have returned to the origins of the country’s greatest universities, too. In 2016, the year that ended with Trump’s first electoral victory, Jonathan Cole, author of The Great American University: Its Rise to Preeminence, Its Indispensable National Role, penned a series of articles in The Atlantic, simultaneously lauding the original mission of elite research universities, criticizing their decadence and misguided policies, and calling for a restoration of meritocracy.[11] In 2021, Stanford historian Emily Levine published the monograph Allies and Rivals: German-American Exchange and the Rise of the Modern Research University; a year later, Michael T. Benson, a friend of Ron Daniels and a university president, too, followed up with Daniel Coit Gilman and the Birth of the American Research University.[12] Both are commendable readings based on substantial archival research. They survey the beginnings of the university, its consolidation, mission, and place within society and the body politic. Although Benson occasionally and Levine more consistently attest to the history of exclusion, they, too, remain wedded to the idea of excellence qua selection of the best and brightest. Inadvertently, they affirm the concept of meritocracy as the foundation of higher education and justification for the outsized role elite universities in the US have played in public life.

By contrast, an honest assessment of universities’ histories that centers exclusion challenges the persistent myth of meritocracy that undergirds higher education, particularly at elite schools which have used the meritocratic mantle to justify their exclusivity. Historically, quality education has represented a prerogative of the elites, who shape, influence, and decide the country’s affairs. Expanded access has never been granted readily and has often coincided with demands for equal political participation by those previously excluded, challenging existing power hierarchies.[13] Centering the archival evidence of exclusion shows that discrimination might not be an inadvertent flaw, a harmless indication of the prevalent Zeitgeist, but systemic and reflective of the history of the US at large.

For a top-notch education, Americans with means travelled to Germany. Between 1815 and 1916, approximately 9,000 Americans, mostly men, studied in Germany; the majority crossed the Atlantic in the 1880s and 1890s. They credited the quick rise of the German Empire to its higher education system

Fascinating Germany

The old American colleges founded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, i.e., Harvard, William and Mary, Yale, Princeton, Penn, “were still primarily moral academies for the inculcation of ‘discipline’ – mental, behavioral, religious,” explains Peter Novick.[14] They distinguished themselves through religious affiliation and varied in organization and governance, while the quality of education was on par with the German “Gymnasium.”[15] For a top-notch education, Americans with means travelled to Germany. Between 1815 and 1916, approximately 9,000 Americans, mostly men, studied in Germany; the majority crossed the Atlantic in the 1880s and 1890s.[16] They credited the quick rise of the German Empire to its higher education system. They learnt from Leopold von Ranke and his disciples, Hermann von Helmholtz and Wilhelm Wundt and others. “The seminar and the laboratory became the structure for advancing new knowledge,” summarizes Jonathan Cole their observation.[17] The German Empire modelled academic practices, standards, and disciplines that they admired and sought to emulate.[18]

America’s First Research University

During a speech as newly minted president of the University of California, Daniel Coit Gilman, born in 1831, called Germany “the United States of the Old World.”[19] Like many of his peers, Gilman aspired not only to learn from the role model but exceed it. As a young man, in 1848, he had enrolled at Yale University, one of the few reputable institutions of higher education in the US at the time. A member of the Skulls and Bones Society, Gilman made formative experiences and lifelong friends in New Haven – many of whom lastingly shaped the US education system. With one of them, Andrew Dickson White, he travelled to Europe in 1853 as attachés to an American legation bound for St. Petersburg. En route, the two visited universities in France, England, and across the German states. In Berlin, for instance, Gilman and White met the geographer Karl Ritter and Leopold von Ranke.[20] Intrigued, Gilman travelled to Europe again in 1855 and 1857.

Gilman assumed his first administrative position at the Sheffield Scientific School in New Haven, where he proved a skillful reformer and fundraiser. When the president of nearby Yale, his alma mater, resigned, Gilman’s name floated as potential successor, but the Board of Trustees considered him “too radical.” Instead, in 1872, he accepted the offer of the presidency of the emerging University of California.[21] He continued his reform drive in the golden state, too, but bumped into opposition from board and faculty members divided over the question whether to prioritize the sciences or a “liberal,” humanist education. A believer in “building character,” Gilman advocated for both: “the boy who is destined to the life of a scholar cannot escape the early study of Mathematics, the foundation of science, and Language, the foundation of the humanities,” he noted in 1881.[22]

Frustrated by the infighting, his friend Andrew Dickson White, by then president of Cornell, relayed unusual news: a man by the name of Johns Hopkins had died in December 1873 without a family, leaving $7 million in stocks of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company to create a university and a hospital to care for “the indigent sick […] without regard to sex, age, or color” in his hometown of Baltimore.[23] The board of trustees that Hopkins had selected before his passing sought advice from “the three most respected and best-known higher education voices”: Charles Eliot of Harvard, James Angell of the University of Michigan, and precisely Andrew Dickson White.[24] Unanimously, they recommended Gilman for president. In 1874, after only two years in California, he accepted the new post, writing to the board members:

The characteristics of your trust are so peculiar & so good that I cannot decline your proposal. The careful manner in which your Board has been selected, the liberal views which you hold in respect to advanced culture in both literature and science, your corporate freedom from political and ecclesiastical alliances & the munificent endowment at your control are especially favorable to the organization of a new University.[25]

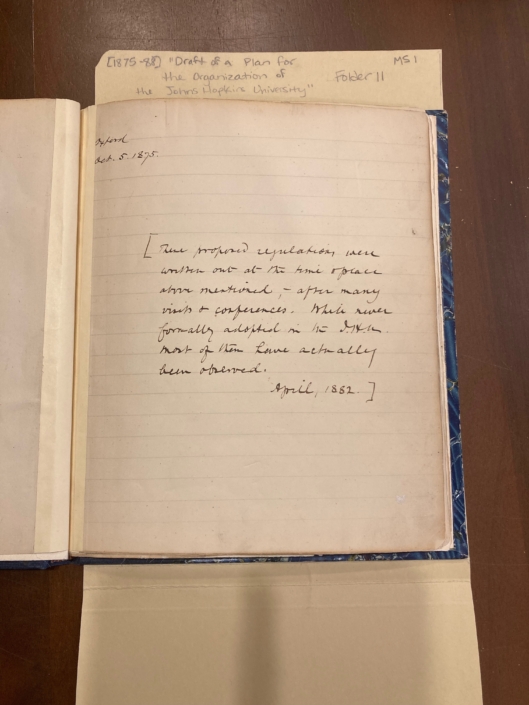

Gilman seized the opportunity to create what had never been done before: a graduate school modelled on the German example.[26] However, he encountered widespread discouragement. “All these administrators failed to remind themselves of what was being done overseas, especially in Germany,” lamented Abraham Flexner in his 1946 Gilman biography.[27] Flexner, son of German-Jewish immigrants, was deemed a reformer himself: in his scathing 1910 report on medical education, he would identify Johns Hopkins School of Medicine as the only “bright spot” in the US.[28] [Img 3 – see the gallery above]

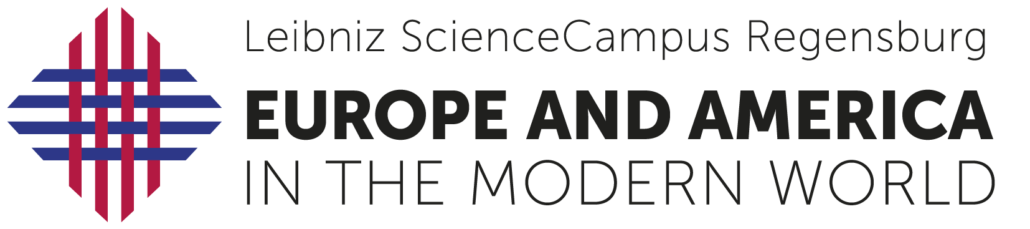

Dozens of notebooks testify to Gilman’s close study of German scholars of education such Heinrich von Sybel, The German Universities: Their Results and Needs (1868), Karl von Hofmann, The Universities in the New German Empire (1871), Ernst Laas, Gymnasium and Realschule; Old Questions Historically Answered (n.d.), and Hermann Bonitz, The Question of Reform in Our Higher Schools (1875).[29] [Img 4 and 5] In 1875, tasked with identifying the most conducive institutional structures and recruit potential faculty, Gilman again boarded a ship to Europe. He sought advice from scientists such as the pathologists Julius Friedrich Cohnheim and Carl Ludwig, the psychologist Wilhelm Wundt in Leipzig, the hygienist Max von Pettenkofer, and the physicists Hermann von Helmholtz and Hugo Kronecken – “a Charming man, & [a] great friend of the Americans,” Gilman noted. He visited Berlin, Munich, Leipzig, Heidelberg, Freiburg, and the new German university in Strasbourg, founded after Alsace-Lorraine’s annexation in 1871. Across the Channel, he consulted with colleagues at Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, Liverpool, and London.[30] Along the way, Gilman drafted a plan for “his” university.[31] [Img 1.1 and 1.2]

On February 22, 1876, the Governor of Maryland, the city’s mayor, President Eliot of Harvard, the board of trustees and other dignitaries gathered in Baltimore’s Academy of Music for Gilman’s inaugural address as Johns Hopkins University president. He had persisted in his vision for a research university, a “Göttingen in Baltimore,” that focused on graduate education.[32] “At a distance,” he remarked, “Germany seems the one country where educational problems are determined; [but] not so, on a nearer look. The thoroughness of the German mind, its desire for perfection in every detail, and its philosophical aptitudes are well illustrated by the controversies now in vogue in the land of universities.” However, the torch had passed, he believed, to the New World. Surveying debates in Tokyo, Beirut, Peking, Egypt and Hawaii, Gilman declared confidently: “The oldest and remotest nations are now looking here for light.”[33] In a city where the vast majority of immigrants and foreign-born residents came from Germany and where German was the second-most spoken language, such stirring words probably sounded true and invigorating. In subsequent decades, JHU faculty would help craft a historical narrative that imagined Americans as heirs to European civilization.

Excellence and Reconciliation

Gilman had attempted to recruit faculty on his trip. He and his peers were intrigued by the perceived excellence and social reverence professors in Germany enjoyed.[34] However, his recruitment efforts failed: “Probably no form of pecuniary aid is more encouraging to a scholar than the surety of a pension. […] Two men of European reputation have declined to come to America on larger salaries than they have every received, assigning as reasons the certainty of pensions if they remained at home,” he explained the advantages of the German professoriate.[35] Gilman though succeeded in one prominent case: when the math genius James Sylvester was denied a degree at Cambridge University because of his refusal to subscribe to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Anglican Church (he was born into a Jewish family), Gilman offered him the inaugural chair of mathematics at Johns Hopkins. Sylvester accepted and, while at JHU, founded the prestigious American Journal of Mathematics.[36]

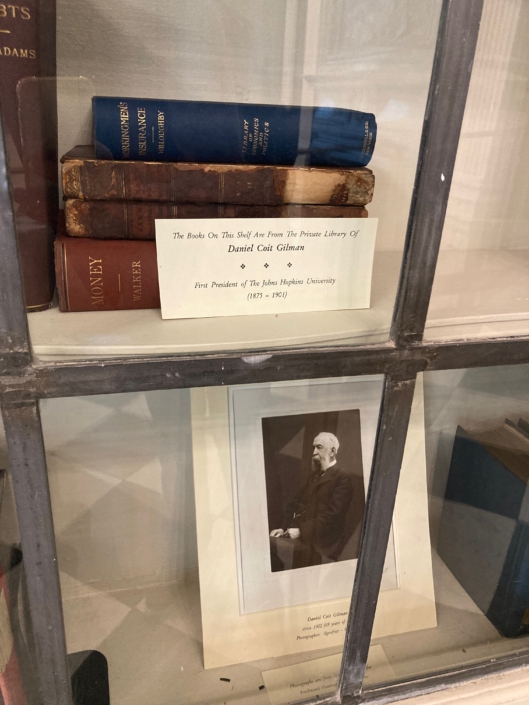

Soon, Gilman hired American faculty members educated in Germany. All of them would leave an indelible mark on US science and academia. Their biographies and activities at Johns Hopkins illustrate the transfer of knowledge and practices from Germany to the US: Among them were Ira Remsen, future co-founder of the American Chemical Journal, who had received his PhD from Göttingen in 1870; the physicist Henry A. Rowland, who just returned from working with Helmholtz in Berlin and went on to co-found the American Physical Society; Basil Gildersleeve, a graduate from Princeton with a PhD from Göttingen, who co-founded the American Journal of Philology; and Herbert Baxter Adams, who held a PhD from the University of Heidelberg, became the first secretary of the American Historical Association (AHA) (Leopold von Ranke became the first honorary member), co-founded the AHA’s flagship journal, the American Historical Review, and established the German tradition of weekly seminars at JHU.[37] [Img 6]

Like other white leaders across the US, the university championed reconciliation between white Northerners and Southerners – at the expense of Black Americans.

However, such an account ignores the university’s exclusivity and more questionable contributions, such as ending Reconstruction and ushering in the period of Redemption. Like other white leaders across the US, the university championed reconciliation between white Northerners and Southerners – at the expense of Black Americans.[38] For instance, the father of classicism in the US, Basil Gildersleeve, had served in the Confederate army and was a lifelong apologist for the “Lost Cause.” He compared the US South to Athens in the Peloponnesian War and continued to publish racist and antisemitic essays, which the university’s press republished in honor upon his retirement in 1915. The case is curious for Johns Hopkins University enjoyed strong support from Baltimore’s German-descending Jewish residents. Many donated generously and sent their sons to study at JHU, one of the only top universities to admit Jewish applicants at the time. Benson writes critically about Gildersleeve’s employment and Gilman’s desire to “heal the breach.”[39] Gildersleeve’s portrait still hangs in the main reading room in Gilman Hall; an explanatory description installed recently. During a book talk between Michael T. Benson and Ron Daniels at the 2023 Alumni weekend, the former challenged the rationale behind keeping the portrait but was left without a response.[40] [Img 7]

The Boys’ Club and Co-education

During his inaugural address, Gilman profusely praised the “liberality” of Baltimore’s leaders and even warned: “they are not among the wise, who depreciate the intellectual capacity of women, and they are not among the prudent, who would deny women the best opportunities for education and culture.”[41] However, Charles Eliot of Harvard had advised the board against coeducation, and they followed his lead.[42] They even axed Gilman’s compromise proposal of a separate college for women following the example of Cambridge so that Gilman retired in 1901 without ever seeing a woman enroll.[43]

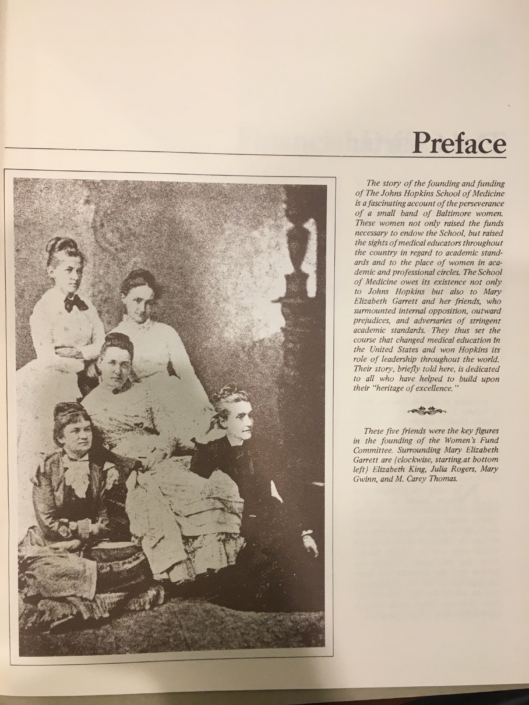

Only financial distress forced a change of mind, albeit within bounds: the 1890 financial crisis had depreciated the endowment to such an extent that it delayed if not threatened the opening of the School of Medicine, modelled on Leipzig. A group of white women with considerable pecuniary means – Martha Carey Thomas, Mary Elizabeth Garrett and three friends, four of whom were daughters of Johns Hopkins’ trustees – offered $500,000 to make up for much of the losses. In return, they demanded opening the school to women. When the final donation drive fell short, Garrett, daughter of the president of B & O Railroad, the same company that had made Hopkins rich, provided the remaining $300,000 and got her wish: The School of Medicine opened its doors in 1898 to white men and women, the latter accounting for three in the inaugural class. Official histories eagerly point to this story of female philanthropy to obfuscate the institution’s long-standing discrimination against women.[44]

Johns Hopkins opened its graduate programs to white women in 1907. Their admission depended on their academic credentials as well as on the benevolence of a professor who endorsed them – granted no other faculty member objected. Such conditionality resembled recent changes in Prussia, which allowed women to apply to universities while granting professors the right to exclude them from classes.[45] Either way, Mary Garrett wrote to President Ira Remsen, Gilman’s successor: “I am sure that there are few of its many friends who are not rejoiced by this coming proof of the liberal attitude of the Board of Trustees and of the head of the University.”[46] Garrett had financially supported the founding of Bryn Mawr, a women’s college in nearby Pennsylvania, under the condition that her friend Martha Carey Thomas would become president. The latter concurred with her benefactor in a separate letter:

The University has honoured itself and has won the gratitude of all liberal men and women by taking this great step voluntarily at just the right time. The opening of its graduate school is the last step in the history of the higher education of women in the United States, and the most important one. They will not now have to go to Germany to get the advanced seminary work offered only by the Hopkins.[47]

Carey Thomas’s claim attests to the persistent appeal of the German model as well as the author’s privileges. She herself had been briefly admitted to Hopkins in 1877 at her father’s insistence but never graduated. Instead, she completed her studies in Germany at a time when only few American women could afford such a venture.[48] The number of American female students in Germany peaked before World War I, but they accounted only for 23 of the 255 Americans in 1911/12.[49] None of that quality education, though, nor her Quaker faith, convinced Carey Thomas, to shed her prejudices: she held deeply racist and antisemitic views that recently forced the Bryn Mawr to reconsider her legacy.[50] [Img 8.1 and 8.2]

Regardless, Johns Hopkins remained a bastion of white male privilege until it embraced undergraduate coeducation in 1970, a year after its peer institutions Yale, Harvard, and Princeton.[51] Ninety-six women, four of whom were Black, joined over 300 freshmen. Most of them were “transfer students,” who had already proven themselves elsewhere. The majority had grown up in Baltimore and continued to live at home and not on campus like their male peers; for years, Hopkins lacked adequate dormitories, restrooms, and services for women (e.g. a gynecologist). But even those who prevailed over the sexist and patriarchal campus culture and earned a PhD at Hopkins were not considered for employment. Only in the 1980s and 1990s did white female professors start breaking through. Yet, Hopkins’ faculty demographics have continued to reveal gross gender and racial inequality.[52]

Hopkins in the Age of Extremes

When World War I broke out, Hopkins struggled to comprehend the changes in a country it had long admired and emulated. The first fall issue of the Hopkins student News-Letter in 1914 sounded almost cheerful: “Half a score of Hopkins professors, who were in Europe at the outbreak of the war,” it reported, “have reached this country in safety.”[53] Dr. Arthur Lovejoy, the eminent historian of ideas, had “used good judgment,” the report continued, “and waited until […] after mobilization” to embark on the way home. The News-Letter relayed the experience of Dr. William Welch, one of the founding professors at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, almost gleefully: on his return trip, in a restaurant in Germany, he found himself accused a British spy. Unperturbed and cunningly, the paper noted, he rose to sing the anti-French war song “Die Wacht am Rhein” – winning over all Germans in the vicinity. [54] [Img 9]

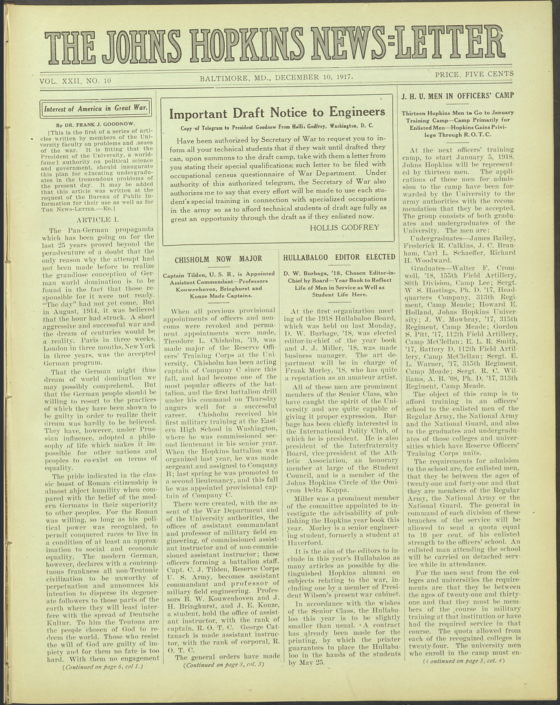

Although several students volunteered to assist the war effort on the side of the Allies, the mood on campus only changed with the US declaration of war in 1917. [55] The News-Letter started publishing letters by (former) students from the frontlines.[56] President Dr. Frank J. Goodnow, Remsen’s successor, who had studied in Berlin and Paris, appealed to students:

The modern German [..] declares with a contemptuous frankness all non-Teutonic civilization to be unworthy of perpetuation and announces his intention to disperse its degenerate followers to those part of the earth where they will least interfere with the spread of Deutsche Kultur. To him the Teutons are the people chosen of God to redeem the world.[57] [Img 12]

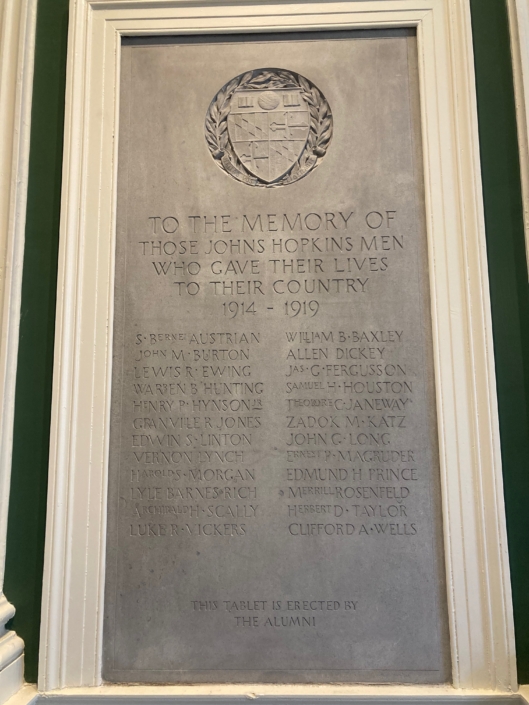

German aggression had to be confronted, otherwise “The fate of Belgium and Northern France may well be ours.” He proclaimed: “Two characteristics have distinguished the modern European life in which we have a share: The first is internationalism, the second is democracy.” He believed Americans, Hopkins’ men specifically, were destined to defend both.[58] [Img 11] One of the university’s alumni, Woodrow Wilson, who had received his PhD from Hopkins in 1896, would bring about the war’s end.

Relations with the Weimar Republic normalized after a few years. In 1931, 415 German students were enrolled at US universities; some 800 Americans studied in Germany. In February 1933, Hopkins recorded students from 45 states, D.C., two dependencies, and 29 different countries, Germany included.[59] The rapid consolidation of the Nazi regime did not immediately translate into concern: in March 1933, the physicist Dr. Karl Herzfeld, Austrian by birth, who had studied in Zürich, Göttingen, and Munich, lectured about the virtues of the German system and still encouraged exchanges.[60] In October 1933, Sir Herbert Louis Samuel, the first Jewish member of a British cabinet, preached composure and reassured an overflowing auditorium that “world conditions did not indicate the ultimate death of democracy.”[61]

Several articles in the News-Letter suggest that not fascism but communism proved the greater irritant.[62] The historian Broadus Mitchell, a member of the Socialist Party, invited known international socialists to preach pacifism and workers’ solidarity in Baltimore. “But,” the News-letter observed, “it was, as usual, an already convinced audience,” workers, “French-speaking people, [..] a handful of Johns Hopkins professors. [..] Few of these would ever go to war. The ones who would did not come,” the paper sneered.[63]

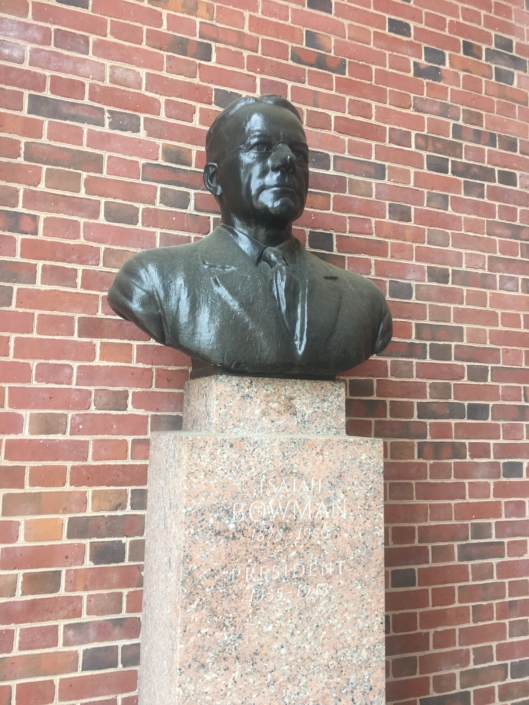

In 1935, the university on the brink of bankruptcy following the Great Depression, Hopkins welcomed a new president, the geographer Isaiah Bowman. National newspapers raved about the choice, and Bowman’s portrait adorned the cover of Time Magazine.[64] The Harvard graduate had established the first geography department of repute at Yale and had presided over the American Geographical Society for twenty years. Moreover, he exuded foreign policy credentials and international experience: Bowman had drawn up the map of Europe with its “proper” ethnic and political boundaries that President Wilson had taken to Versailles in 1919.

The Office of Education promptly asked Bowman to chair a subcommittee to reassess graduate education in post-Great Depression America, trusting JHU again to spearhead educational reforms. In the final report, Bowman elaborated on the intricate relationship between education and democracy:

By democratic do we not really mean democratic enough to suit the majority? The term democratic, used in a realistic sense, includes not all of the people but only those effectives who contribute to the democratic process. […] a few men in all systems tend to exercise control within limits set by ideals, social tolerance, and drift. […] As a part of the social machinery the schools should recognize their responsibilities in explaining how democracy really works, lest words and idealizations detached from realities take the place of understanding.[65]

A proud elitist, Bowman shared such patronizing, quintessentially undemocratic views openly. One can assume that many in the country’s elite concurred: only educated white men, like those at Hopkins, were destined to govern and decide America’s public affairs.[66] [Img 14]

Shortly after the German attack on Poland in 1939, President Bowman impressed upon Hopkins’ students the virtues of the Versailles Treaty, especially the principle of self-determination. He blamed the outbreak of another war in Europe on the failure to create truly homogenous nation-states.[67] He reiterated the position in an article in the Geographical Review, in which distinguished between American geography (good) and German geopolitics (bad) by condemning Germans’ inclination to violence and celebrating American democracy as morally superior.[68]

Bowman was also unapologetically antisemitic.[69] As US troops fought fascism in Europe, and students protested antisemitism at a nearby swim club, Bowman introduced an anti-Jewish quota in 1942.[70] A reality at many elite universities before the war, most had not only started dropping theirs but also welcomed Jewish-born “refugee scholars” from Europe, especially Germany, to enrich science, research and teaching.[71] The opposite happened at Johns Hopkins under Bowman, despite decades of support from Baltimore’s Jewish community.[72] Many had immigrated from Germany in the mid-19th century and quickly assimilated the values of the white Protestant establishment. Case in point is the Hutzler family, who counted among the most prominent supporters of the university since its founding.[73] Shortly before Bowman’s appointment, at the encouragement of Judge Eli Frank, a member of the university’s board, Jewish Baltimoreans staked the salary of James Franck, a renowned physicist and Nobel laureate, who had been dismissed as director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at Göttingen under the Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service. [74] Abraham Flexner and others sent their commendations on the appointment.[75]

Although Bowman’s antisemitism had been known, it had not deterred his appointment at Johns Hopkins. Within a year of his arrival, he affected the departure of Franck, Karl Herzfeld and another scholar; Bowman personally also blocked the appointment of historian Eric Goldman.[76] According to his biographer, Bowman complained to the dean, G. Wilson Shaffer, that the university was turning into a “Jewish institution.”[77] “Jews don’t come to Hopkins to make the world better or anything like that,” he allegedly said. “They come for two things: to make money and to marry non-Jewish women.”[78] Regardless, in late 1938, President Roosevelt appointed him to a commission at the State Department tasked with planning the relocation of Jewish refugees from Europe.[79] In 1942, Bowman, the “worst antisemite in the State Department,” according to James Loeffler, founded the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) to support the war effort with research in weapons systems and technology.[80] APL represents a lasting legacy, due to which Hopkins remains the largest recipient of federal defense research funding. That same year, 1942, however, Bowman also tasked Shaffer with limiting the enrollment of Jewish students.

The anti-Jewish quota represents a peculiar anachronism. Jason Kalman documents some resistance to the policy within Hopkins and among the city’s Jewish community. But neither staged a public uproar nor deserted the university. Instead, Kalman points to a “pact” between Bowman and Baltimore’s wealthy, German-descending Jews: their sons would still be admitted. “Only” the offspring from poorer, more recent East European Jewish immigrants would be denied, regardless of their qualifications. Baltimore’s Jewish leaders acquiesced into such “class complicity”, Kalman argues, because they sought to appease Bowman who – like them – opposed post-war Zionist ambitions for Palestine. They wanted to belong, not emigrate or be singled out for their religious background.[81]

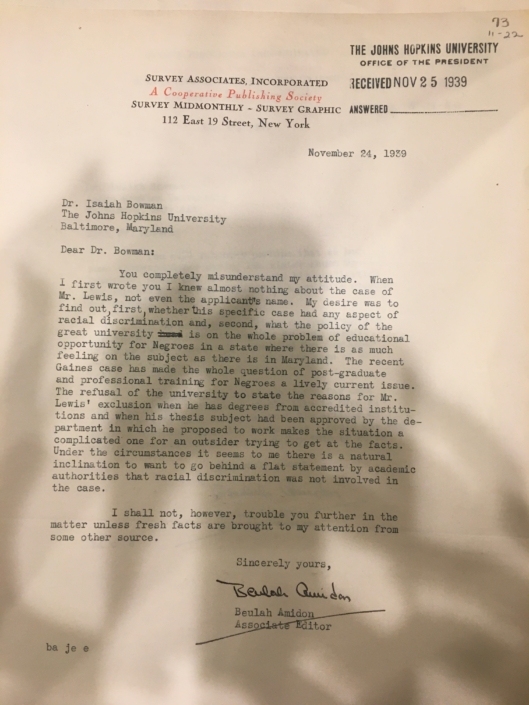

Paradoxically, Bowman, an antisemite and racist, even enlisted Eli Franck, the aforementioned judge, in thwarting the campaign on behalf of a Black male graduate applicant who would have broken Hopkins’ color barrier.[82] In 1939, Edward S. Lewis, a graduate of the University of Chicago, had secured a faculty advisor at Hopkins and applied for admission. He desired to move to Baltimore where he had been named secretary of the Urban League. However, his credentials notwithstanding, the Academic Council rejected his application, probably under pressure from Bowman.[83] The Afro, the country’s oldest, Black family-owned newspaper, and Beulah Amidon, a journalist and member of the National Women’s Party, covered the story, much to Bowman’s displeasure. Amidon contacted Judge Franck and other city notables. However, the former briefed Bowman and, in 1945, assured the president that for him the matter was settled, neither would Ms. Amidon be received nor Lewis’ case considered.[84] [Img 15 and 16]

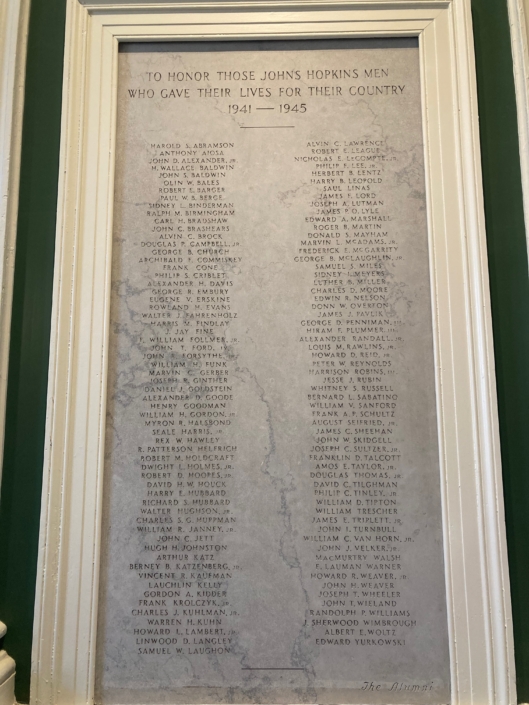

The first Black undergraduate student, Frederick I. Scott, enrolled at Johns Hopkins University in 1945, sixty-nine years after its founding, with Bowman still president – but away in San Francisco. On his application form, Scott expressed his desire to join “the finest university in the country” and promised, as others before him, to do his utmost to succeed and further the university’s renown.[85] As the number of Black students grew incrementally, the cohort in the late 1960s and early 1970s, called itself the “Fred Scott Brigade.”[86] In 1969, in need of a “safe space” within a largely unwelcoming environment, they founded the Black Student Union. For decades, the proportion of students who identified as Black or African American at Johns Hopkins hovered around 3-5 per cent, far below the population, while Black faculty remained a rare sight well into the 21st century.

Neither his racism nor his antisemitism precluded Bowman from any opportunities, honors or government employment. In April 1945, the US Secretary of State appointed him an advisor to the US delegation to the upcoming conference in San Francisco, where the United Nations Organization were founded.[87] Although Bowman retired in 1948, the anti-Jewish quota only fell in 1950, when Albert Hutzler, scion of the prominent Baltimore family, threatened to reject an invitation to the board of trustees if the discriminatory admissions practice was not abolished. The quota was silently suspended. In 1958, the Jewish Student Association was founded. In 1972, Steven Muller, born in Hamburg in 1927, became Johns Hopkins’ tenth president. His family had fled to the US via England in 1939. In 1998, Hopkins Hillel was established, and today counts about 400 Jewish students, approx. 10 per cent of the entire student population, on campus.[88] In 2009, Ron Daniels arrived as JHU’s fourteenth president, the third who identifies as Jewish.[89] For years, however, Daniels has objected to demands to remove a bust of Bowman, which sits in front of a prestigious campus building, and rename Bowman Drive. In 2024, three scholars – Sanford Jacoby, Paige Glotzer, and Laurel Leff – published two prominent articles to put pressure on the university and submitted a detailed report to the JHU Name Review Board, to effect change.[90]

Conclusion

Contrary to the idea of meritocracy as the perennial and enduring foundation of higher education, archival evidence suggests it has been rather an ideal than a lived reality

After World War II, the “torch” that Gilman had mentioned in 1876 indeed passed on to the US.[91] As the Cold War heated up, federal investments in research and science rose exponentially. Johns Hopkins, the country’s first research university, benefitted considerably and consolidated its excellence and exclusivity. Less than 8 per cent of applicants get accepted – a rate generally considered a sign of excellence. Faculty and alumni have collected a total of 29 Nobel Prizes, eight Presidential Medals of Science, and hundreds of other prestigious recognitions. JHU has led the country in research spending for forty-four years and has continuously ranked among the world’s best universities.

In 2013, Johns Hopkins started to suspend legacy admission, a hereditary privilege that gives children of alumni a leg up and is still a common practice at many elite universities, such as Harvard. In 2024, former First Lady Michelle Obama called it “affirmative action for the wealthy.”[92] Johns Hopkins’ decision was made public only in 2020, when sufficient data had been collected to prove that the quality of students had not declined – an argument often raised in favor of maintaining legacy, mostly leveraged by influential alumni.[93] Daniels has been adamant about his decision: Legacy admission would violate “the Jeffersonian ideal of equal opportunity and merit.”[94] In 2009, when his tenure began, “the incoming class had more students with legacy status than it had students who qualified for Pell grants.”[95] By 2020, without legacy preference, less than 4 per cent still held a legacy connection, while 20 per cent of students qualified for Pell grants.[96] Such data suggests that, hitherto, meritocracy was practiced only conditionally.

Between 2019 and 2023, students from minority backgrounds and underrepresented groups have increased considerably. Every fifth student starting in 2023 was the first in their families to go to college. About the same number did not speak English at home. Thirty per cent of students in the class of 2027 (their planned graduation year) identified as Asian-American, twenty-one as Hispanic or LatinX, and sixteen per cent as white and Black/ African American. They all graduated in the top ten per cent of their high school classes and had passed the comprehensive admissions process.

Such dramatic changes were facilitated by the largest donation in US higher education history: In November 2018, Michael R. Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York City and Republican presidential candidate, donated $1.8 billion to his alma mater.[97] “No qualified high school student should ever be barred entrance to a college based on his or her family’s bank account. Yet it happens all the time,” he justified the gift in the New York Times undermining the myth of meritocracy.[98] Bloomberg’s donation allowed JHU to adopt a “needs-blind admissions process” that has radically changed the composition of the student body. “Financial circumstances shouldn’t limit your potential,” concurs the JHU Office of Admission as it instituted a more comprehensive assessment of applicants.[99] Students, who cannot afford the price tag of $65k, will have 100% of their need covered by a scholarship, not a loan, i.e. they will not have to repay it. In 2023, more than half of JHU undergraduate students received financial aid; scholarships averaged $64,000 annually.

However, as soon as the undergraduate student body had diversified, the Supreme Court considered the case “Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard University,” a challenge to affirmative action, a policy introduced during the civil rights era to account for historic injustice.[100] In 2018, together with fifteen other elite universities, JHU filed an amicus brief in defense of the practice.[101] Regardless, the Supreme Court’s majority sided with the plaintiffs and, in June 2023, ended affirmative action nationwide. For the academic year 2024/2025, race could not be considered in college applications at all.

The impact of referenda ending affirmative action in California in 1996 and in Michigan in 2006 made the consequences of the Supreme Court’s ruling predictable. Although race represents only one among many factors in the admissions process, the change in JHU’s incoming class of 2028 was dramatic: fewer than six per cent of students identify as Black and fewer than 11% as Hispanic, signifying a drop, proportionately, of ten and almost twenty per cent respectively. Meanwhile the share of Asian American students increased to 46 and white students to 34 per cent. Only the number of first-generation college students has been maintained.[102]

The above account centers exclusionary practices and policies. It shows that meritocracy has historically not been a reality at Johns Hopkins University, a case that is representative for elite universities in the US at large. The many research accomplishments notwithstanding, the university’s decade-long protection of privileges for the few resulted in the preservation of a very white and very wealthy student (and faculty) body well into the 21st century – despite the formal existence of affirmative action.[103] The above story of exclusions demonstrates that for long JHU and other US universities have prevented opportunities and careers and kept bright minds from fulfilling their true potential. Contrary to the idea of meritocracy as the perennial and enduring foundation of higher education, archival evidence suggests it has been rather an ideal than a lived reality in JHU’s history. The changes between 2020 and 2023 notwithstanding, the latest statistics reveal the long-term chilling effect of discriminatory policies and exclusionary practices. With a re-homogenization of the student population afoot, student organizations articulated their concerns over the demographic shift.[104] To appease a concerned student body, the president sat for an interview with the News-Letter in December 2024, proposing few tangible solutions.[105]

since the inauguration of the second Trump administration, the university – as many others, most prominently Harvard – has come under sustained attack: the federal government has weaponized the fight against antisemitism and disproportionately threatens sixty universities, including JHU, to withhold all federal funding

Moreover, since the inauguration of the second Trump administration, the university – as many others, most prominently Harvard – has come under sustained attack: the federal government has weaponized the fight against antisemitism and disproportionately threatens sixty universities, including JHU, to withhold all federal funding.[106] The dissolution of USAID, the cuts to the National Institutes for Health, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and other grant-giving agencies has caused JHU to lose around $1 billion in funding this spring alone.[107] Thirty-seven Hopkins graduate students had their visas arbitrarily revoked in March and then reinstated by a judge three weeks later.[108]

In the current political climate, a future in which the university and its peers fully acknowledge their past and qualify their rhetoric around meritocracy accordingly, seems unlikely. In May, in an atmosphere of intimidation and financial uncertainty, the university administration resolved to use earnings from its $13.5 billion endowment to compensate for the loss of federal grants and allow oftentimes life-saving research to continue.[109] With the federal government’s war on DEI and universities as such, more proactive changes to the admission policies, let alone hiring, are unlikely; they could easily attract further “unwanted” attention from a federal government aggressively seeking control. What that means for the viability of US universities as attractive places to study, work, and research for any and all regardless of race, gender, nationality, religion, sexual orientation or class remains to be seen.

Notes & References

[1] “Johns Hopkins Awards Honorary Degree to German Chancellor Angela Merkel,” (Youtube: Johns Hopkins University, 2021). https://youtu.be/vryWPISY-xM?si=XHpCKptAVzgNOjR9. Not accidentally, the ceremony teased ideas on which Daniels elaborated in his then upcoming book, What Universities Owe Democracy. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021).

[2] “Angela Merkel receives Johns Hopkins ‘Doctorate of Humane Letters’ | DW News,” July 15, 2021. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gkRK6J3Iew4. Also see “Angela Merkel Receives Johns Hopkins Honorary Degree,” The Hub (July 15, 2021). https://hub.jhu.edu/2021/07/15/angela-merkel-receives-honorary-degree/.

[3] “Angela Merkel receives Johns Hopkins ‘Doctorate of Humane Letters’ | DW News,” July 15, 2021. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gkRK6J3Iew4.

[4] See e.g. “Angela Merkel publishes blunt memoir ‘Freedom’,” DW (November 25, 2024). https://www.dw.com/en/angela-merkel-publishes-blunt-memoir-freedom/a-70881556. Note that Daniels begins his deliberations in his monograph with a visit to Budapest where the Central European University had just been shut down. Ronald J. Daniels et al., What Universities Owe Democracy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021), 1-5. Also see Ronald J. Daniels, “Opinion: Why Authoritarian Regimes Attack Independent Universities,” Washington Post, 28 September 2021.

[5] Since the early 2000s, newspapers and magazines, including the New York Times, Washington Post, the New York Review of Books and the Chronicle of Higher Education have rung the alarm bells about the abysmal financial state of public higher education in the US. See also Cole, Jonathan R. “The Pillaging of America’s State Universities.” The Atlantic (2016). Published electronically April 10, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/04/the-pillaging-of-americas-state-universities/477594/.

[6] Golden, Daniel. The Price of Admission: How America’s Ruling Class Buys Its Way into Elite Colleges – and Who Gets Left Outside the Gates. New York: Crown Publishers, 2006.

[7] Daniels et al., What Universities Owe Democracy, 39 and 40.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ronald Daniels, “Why We Ended Legacy Admissions at Johns Hopkins. Eliminating an Unfair Tradition Made Our University More Accessible to All Talented Students,” The Atlantic (2020), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/01/why-we-ended-legacy-admissions-johns-hopkins/605131/. Daniels et al., What Universities Owe Democracy, 143.

[10] Thanks to a PhD student and an assistant professor who developed the worldwide first Covid-19 tracker map, Johns Hopkins University contributed significantly to combatting the pandemic.

[11] Cole, Jonathan R. “Why Elite-College Admissions Need an Overhaul.” The Atlantic (2016). Published electronically February 14, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/02/whats-wrong-with-college-admissions/462063/. Cole, J. R. “Why Sports and Elite Academics Do Not Mix.” The Atlantic (2016). Published electronically March 9, 2016. ttps://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/03/the-case-against-student-athletes/518739/. Cole, J. R. “The Triumph of America’s Research University.” The Atlantic (2016). Published electronically September 20, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/09/the-triumph-of-americas-research-university/500798/.

[12] Emily Levine, Allies and Rivals. German-American Exchange and the Rise of the Modern Research University (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021); Michael T. Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman and the Birth of the American Research University (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022); Daniels et al., What Universities Owe Democracy.

[13] Jack Schneider and Jennifer Berkshire, A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door: The Dismantling of Public Education and the Future of School (New York, NY: The New Press, 2023); Noliwe M. Rooks, Cutting School: Privatization, Segregation, and the End of Public Education, (New York ;: The New Press, 2017).

[14] Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The ‘Objectivity Question’ and the American Historical Profession (Cambridge University Press, 1988), 22.

[15] John S. Brubacher and Willis Rudy, Higher Education in Transition. A History of American Colleges and Universities, 1636-1968 (New York, Evanston, London: Harper & Row Publishers, 1968), 183-85.

[16] Dietrich Goldschmidt, “Historical Interaction between Higher Education in Germany and in the United States,” Werkstattberichte 36, no. German and American Universities: Mutual Influence – Past and Present (1992): 14. Hart, James Morgan. German Universities: A Narrative of Personal Experience. New York: G.P. Putnam & Sons, 1874.

[17] Cole, The Great American University, 17. Also Levine, Allies and Rivals, 7.

[18] Levine, Allies and Rivals, 4, 21-33. By contrast, Bernd Henningsen claims that federalism brought about German universities’ decline. Bernd Henningsen, “A Joyful Good-Bye to Wilhem Von Humboldt: The German University and the Humboldtian Ideals of ‘Einsamkeit Und Freiheit’,” in The European Research University, ed. Kjell Blückert, Guy Neave, and Thorsten Nybom (New York, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006), 93.

[19] Quoted in Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman and the Birth of the American Research University, 61.

[20] Abraham Flexner, Daniel Coit Gilman: Creator of the American Type of University (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1946), 6-8.

[21] Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman, 43-81.

[22] “The Idea of the University”, Box: 1-63 [31151030055192], Folder: 13 (Mixed Materials). Daniel Coit Gilman papers, MS-0001. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/166234.

[23] Alongside his Quaker faith, the quote in Hopkins’ letter to the trustees has been leveraged as proof of his magnanimity and abolitionism. However, in 2020, researchers discovered census records from the mid-19th century that list enslaved people among his household. For more, see Martha S. Jones, “Johns Hopkins and Slaveholding. Preliminary Findings,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2020).

[24] Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman, 82-105.

[25] Quoted in Warren, Johns Hopkins. Knowledge for the World, 3. [my emphasis]

[26] Daniels acknowledges Gilman’s admiration for the German university model “as a center of original thinking, research, and discovery.” Daniels et al., What Universities Owe Democracy, 143.

[27] Flexner, Abraham. Daniel Coit Gilman: Creator of the American Type of University. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1946. Flexner received an honorary doctorate from Johns Hopkins University in 1949.

[28] Levine, Allies and Rivals, 118. Flexner, Abraham. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. New York: Carnegie Foundation, 1910.

[29] Notes and notebooks, 1852-1905. Daniel Coit Gilman papers, MS-0001. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/129654.

[30] People to visit in Europe, Box: 1-61 [31151030055176], Folder: 7 (Mixed Materials). Daniel Coit Gilman papers, MS-0001. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/166217. On Pettenkofer’s career and controversial legacy, see Mathias Schütz, “After Pettenkofer. Munich’s Institute of Hygiene and the Long Shadow of Naitonal Socialism, 1894-1974,” International Journal of Medical Microbiology, no. 310 (2020). For more on Gilman’s reconnaissance, see Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman and the Birth of the American Research University, 117-20.

[31] Draft of A Plan for the Organization of Johns Hopkins University, 1875-1888, Container: 2-1 [aspace.129654.box.2-1], Folder: 12 (folder). Daniel Coit Gilman papers, MS-0001. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/129666.

[32] Daniel Coit Gilman, Inaugural Address of Daniel Coit Gilman, 1876 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), 27.

[33] Ibid., 11-13. For reach of the German university model, see Jürgen Osterhammel, Die Verwandlung Der Welt. Eine Geschichte Des 19. Jahrhunderts, 3rd ed. (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2009), 1140-41.

[34] Novick, That Noble Dream, 22-31.

[35] “The Idea of the University”, Box: 1-63 [31151030055192], Folder: 13 (Mixed Materials). Daniel Coit Gilman papers, MS-0001. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/166234. [Quote p. 365].

[36] Levine, Allies and Rivals, 47. Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman and the Birth of the American Research University, 120-27. Exceptionally, Sylvester accepted and graduated a female PhD student named Christine Ladd.

[37] On the AHR and Baxter Adams’ faith in finding historical truth à la Ranke, see Novick, That Noble Dream, 26, 33. For the recruitment of the initial seven faculty, see Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman, 106-39.

[38] Ibid., 108.

[39] Ibid., 128-35. Also see Denise Eileen McCoskey, “Basil Gildersleeve and John Scott: Race and the Rise of American Classical Philology,” American Journal of Philology 143, no. 2 (2022). For the collection of essays published in honor of his retirement, see Basil L. Gildersleeve, The Creed of the Old South (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University, 1915).

[40] Instead of responding, Daniels quickly changed the topic of conversation. See the Alumni weekend’s schedule https://alumni.jhu.edu/alumni-weekend-2023-schedule-events.

[41] Gilman, Inaugural Address of Daniel Coit Gilman, 1876, 32.

[42] Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman, 100.

[43] Gilman, Inaugural Address of Daniel Coit Gilman, 1876, 8, 32-33. Goucher College for women, located further north, was not founded until 1885. Historically, it has played a subservient role to Hopkins and was hitherto often used to deflect and deter calls for coeducation. Warren, Johns Hopkins. Knowledge for the World, 98-99.

[44] For the centennial, Hopkins issued a commemorative brochure, “The Women’s Medical Fund and the Opening of The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine,” which celebrated the women’s philanthropy and persistence, a fig leaf at a time when women were still underrepresented among students and, even more so, faculty. “Women’s Fund Memorial Building, 1979,” Box: 14-58, Folder: 36. Office of the President records, RG-02-001. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/94358 Accessed January 03, 2025. For the latest installments see Benson, Daniel Coit Gilman, 80.

[45] Louis Menand et al., eds., The Rise of the Research University. A Sourcebook (University of Chicago Press, 2017), 313.

[46] Letter from Mary Garrett, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, to Ira Remsen. April 13, 1907. Women Graduate Students, Admission of [167], 1904-1919. Office of the President records. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/76685

[47] Letter from M. Carey Thomas to President Ira Remsen, April 12, 1907. “Women Graduate Students, Admission of [167], 1904-1919”. Office of the President records. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/76685.“

[48] Göttingen opened its doors to German women in 1894, universities in Baden only in 1900 and in Bavaria in 1903. The inferior position of women and the dismissive attitude towards women’s education at German universities inspired a passionate exchange in The Nation in 1894, reprinted in Menand et al., The Rise of the Research University. A Sourcebook, 320-27.

[49] Goldschmidt, “Historical Interaction between Higher Education in Germany and in the United States,” 14.

[50] “Racist, Anti-Semitic Champion of Women’s Education,” Inside Higher Ed, August 9, 2018. URL: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/08/09/bryn-mawr-reconsiders-how-it-has-honored-its-bigoted-second-president. “How Should We Remember M. Carey Thomas?” Bryn Mawr Alumni Bulletin, Fall 2017. URL: https://www.brynmawr.edu/bulletin/how-should-we-remember-m-carey-thomas.

[51] “Committee on Coeducation, 1969-1970,” Container: 1, Folder: 6. Academic Council of Homewood Faculties records, RG-04-010. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/84666.

[52] Gabrielle Spiegel earned her graduate degree at Harvard and a PhD from JHU in 1974, yet she recalls that her professors were flabbergasted when she pointed out the irony of getting a degree from an institution that would not find her worthy of hiring as a professor. She taught at Bryn Mawr, her alma mater, and eventually became a professor at Hopkins in 1993. The daughter of Austrian Jewish immigrants was elected president of the American Historical Association in 2007. In 2024, the organization elected Thavolia Glymph as its 140th president, the first Black woman to hold that office. Curiously, Daniels does not discuss his institution’s gender discrimination, although he mentions Title IX. See Daniels et al., What Universities Owe Democracy, 216.

[53] “Dr. Welch Sings in Berlin,“ News-Letter (October 12, 1914): 2. URL: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/38447/1914_019_001.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[54] Ibid. Note that Welch, a former student of Julius Cohnheim and Rudolf Virchow, believed in eugenics. His racist views influenced his research and medical practice to the detriment of Black patients.

[55] “News-Letter Changes Hand,” JHU News-Letter, (December 3, 1917): 1. URL: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/38505/1917_022_009.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[56] “Letters from Men in Service,” Ibid., p. 4, 6.

[57] Dr. Frank J. Goodnow, “Interest of America in Great War,” News-Letter (December 10, 1917): 1.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Goldschmidt, “Historical Interaction between Higher Education in Germany and in the United States,” 21-24. “Representatives of 29 Foreign Countries Among Students here,” JHU News Letter (February 17, 1933): 1.

[60] “Dr. Karl Herzfeld to Present Illustrated Lecture At Assembly,” JHU News-Letter (March 3, 1933): 1. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/41386/1933_37_28.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. For more on the recovery of German-American exchanges before 1933, see Levine, Allies and Rivals, 206-10.

[61] “The World Not Going Fascist,” Says Samuels, British Statesman,” JHU News-Letter (October 13, 1933). https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/41401/1933_38_04.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[62] “Dr. Blumberg Gives Series of Lectures to John Reed Club, JHU News-Letter (March 24, 1933): 2. “Dictatorship of the Proletariat scored by Joel Seidman,” JHU News-Letter (April 28, 1933) 1. URL: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/41390/1933_37_34.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. In late 1935, President Bowman received a threatening, anonymous note supposedly about a meeting of influential lawyers and bankers. It read: “If we cannot have our sons led by American ideas rather than Russia then you lose our moral and financial aid.” In LSC RG.01.001 vol/boxes: 2-11, Board of Trustees, Supportive Documents, folder 12-1, 1/1/25-12/7/35, Executive Committee, Board of Trustees, Information for Meetings.

[63] “Famous Radicals Don’t Interest Baltimore; Dr. Mitchell Speaks,” JHU News-Letter (October 13, 1933): 1. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/41401/1933_38_04.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. For Mitchell’s clashes with President Bowman, see Neil Smith, American Empire: Roosevelt’s Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 247-48.

[64] Ibid., 242. “Education: Scholars Without Money,” Time Magazine, March 23, 1936.

[65] Isaiah Bowman, The Graduate School in American Democracy (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior, 1939), 37. [Author’s emphasis]

[66] Smith, American Empire, 241-44.

[67] “Bowman Speaks on Europe in Dormitory,” JHU News-Letter (October 20, 1939): 1. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/44392/1939_44_18.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y..

[68] Bowman, Isaiah. “Geography Vs. Geopolitics.” Geographical Review 32, no. 4 (1942): 646-58.

[69] Loeffler, James. Rooted Cosmopolitans: Jews and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 115.

[70] “Student Council Protests Meadowbrooks Anti-Semitism,” JHU News-Letter, vol 46, no. 2 (September 4, 1942). URL: http://jhir.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/45507.

[71] Levine, Allies and Rivals, 218-46. Louis Menand, The Free World. Art and Thought in the Cold War (New York: Picador. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2021), 160-62.

[72] Special meeting minutes in LSC RG.01.001 vol/boxes: 2-11, Board of Trustees, Supportive Documents, folder 11-3, 2/22/35 and Board of Trustee meeting minutes folder in 11-4, 3/4/1935. Jason Kalman, “Dark Places around the University: The Johns Hopkins University Admissions Quota and the Jewish Community, 1945-1951,” Hebrew Union College Annual 81 (2010).

[73] Advertising for the Hutzler department store regularly adorned the pages of the News-Letter. For more, see “The Hutzler Experience,” Maryland Center for History and Culture, URL: https://www.mdhistory.org/the-hutzler-experience/. Rosemary Hutzler Raun, “An Elegy for a Hutzler Estate,” Baltimore Sun, URL: https://digitaledition.baltimoresun.com/tribune/article_popover.aspx?guid=fd91dcd2-da87-4860-b9d1-b66ab9b00247.

[74] Levine, Allies and Rivals, 200-03.

[75] Letters attached to minutes of Executive Committee meeting, February 4, 1935. “Board of Trustees. Minutes and Supporting Papers. January 1935-July 1935,” R.G. No. 01, Box No. 11, Ferdinand Hamburger, Jr. Archives.

[76] Kalman, “Dark Places around the University: The Johns Hopkins University Admissions Quota and the Jewish Community, 1945-1951,” 12. Smith, American Empire, 245.

[77] Smith, American Empire, 247.. Kalman sifts through the numbers floated, and suggests that although Jewish students were disproportionately represented at JHU previously, Bowman operated with exaggerated numbers. Kalman, “Dark Places around the University: The Johns Hopkins University Admissions Quota and the Jewish Community, 1945-1951,” 254-55, 59-63.

[78] Ibid. “Student Council Protests Meadowbrook Anti-Semitism,” JHU News-Letter (September 4, 1942): 1. URL: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/45507/1942_46_02.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Morgan Ome, “A legacy of anti-Semitism,” The Johns Hopkins News-Letter (March 3, 2016). https://www.jhunewsletter.com/article/2016/03/a-legacy-of-anti-semitism.

[79] Tara Zahra, The Great Migration: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2016), 161-63.

[80] Smith, American Empire, 237. Also see “Bowman to engineers, study that is patriotism,” JHU News-Letter (December 12, 1941): 1. URL: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/44424/1941_45_09.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. More in “The Revolution in Federal Science Policy,” Hugh Davis Graham and Nancy Diamon, The Rise of the American Research University (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 26-49.

[81] Kalman, “Dark Places around the University,” 19-20. Loeffler, Rooted Cosmopolitans, 83-168.

[82] Some historians of JHU point to Kelly Miller, a Black math student whom Gilman had admitted, and who later became a dean at Howard University as the first person of color to attend Hopkins. However, Miller never graduated, lacking the financial means and a scholarship.

[83] Neil Smith discusses Bowman’s strong dislike of Mitchell, who ran for president on the socialist party’s ticket in 1934. Curiously, his running mate was Elisabeth Gilman, the inaugural president’s daughter. Smith, American Empire, 2247-250.

[84] Correspondence in “Negro Education [73], 1939 November – 1948.” Office of the President records. Special Collections. https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/76577. Smith mistakenly claims that Lewis resigned and did not inform the press. The biographer might have failed to check the city’s Black newspaper. Ibid., 247-48.

[85] “Remembering Frederick Isadore Scott, Johns Hopkins’ First Black Undergraduate,” The Afro (2017), https://afro.com/remembering-frederick-isadore-scott-johns-hopkins-first-black-undergraduate/; Katie Pearce, “Frederick Scott, Who Became Johns Hopkins’ First Black Undergraduate Student in 1945, Dies at 89,” JHU HUB (2017), https://hub.jhu.edu/2017/07/20/frederick-scott-johns-hopkins/.

[86] “Residential Tower Named in Honor of Pioneering Figure Frederick Scott,” The Hub (2022), https://hub.jhu.edu/2022/10/04/scott-tower-dedication-names-narratives/.

[87] James Loeffler, “”The Conscience of America”: Human Rights, Jewish Politics, and American Foreign Policy at the 1945 United Nations San Francisco Conference,” Journal of American History 100, no. 2 (2013).

[88] See https://hopkinshillel.org/.

[89] Daniels’ father fled to Canada in spring 1939, as he recounts in Daniels, What Universities Owe Democracy, vii-viii. For more on Jewish students at JHU, see “Jews at Hopkins: A Digital History,” by Michael Anfang, 2018. URL https://exhibits.library.jhu.edu/exhibits/show/jews-at-hopkins.

[90] Jacoby, Sanford, and Laurel Leff. “Why Is Johns Hopkins Still Honoring an Antisemite?” Chronicle of Higher Education (2024). Published electronically February 22, 2024. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-is-johns-hopkins-still-honoring-an-antisemite.nJacoby, Sanford, Laurel Leff, and Paige Glotzer. “The Most Antisemitic University President You’ve Never Heard Of.” Forward (2024). Published electronically October 17, 2024. https://forward.com/opinion/665419/isaiah-bowman-johns-hopkins-antisemitic/. For more on the NRB, see https://www.jhu.edu/name-review-board/.

[91] John Krige, American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2006). JHU reinvigorated the relationship with (West) Germany when it founded the American Center for German Studies, now American-German Institute, in 1983, and recognized President Richard von Weizsäcker and Rita Süssmuth with honorary degrees in the 1990s.

[92] “Watch: Michelle Obama Speaks at 2024 Democratic National Convention | 2024 Dnc Night 2,” in PBS Newshour (USA: Youtube, 2024). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YgJBFBwRXvc.

[93] Golden, The Price of Admission, 21-48, 285-297.

[94] Daniels et al., What Universities Owe Democracy, 30. Daniels, “Why We Ended Legacy Admissions at Johns Hopkins”.

[95] Note: Federal Pell grants helps students from low-income households to pay for college. Saralyn Cruickshank, “Jhu Ends Legacy Preference in Admissions,” The Hub (2020), https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2020/spring/ending-legacy-admissions/.

[96] Ibid.

[97] Anemona Hartocollis, “Bloomberg Gives $1.8 Billion to Johns Hopkins for Student Aid,” New York Times, November 18, 2018 2018. For a more critical take on the donation, see Dylan Matthews, “The Tragedy of Michael Bloomberg’s Latest Act of Mega-Philanthropy,” Vox (2018), https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2018/11/19/18102994/michael-bloomberg-johns-hopkins-financial-aid-donation. In July 2024, Bloomberg followed up with a $1 billion donation to cover tuition for all students at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

[98] Michael R. Bloomberg, “Why I’m Giving $1.8 Billion for College Financial Aid,” New York Times (2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/18/opinion/bloomberg-college-donation-financial-aid.html.

[99] “Tuition & Aid,” Office of Undergraduate Admission, Johns Hopkins University (2024). https://apply.jhu.edu/tuition-aid/.

[100] See SSFA’s website https://studentsforfairadmissions.org. “He Worked for Years to Overturn Affirmative Action and Finally Won. He’s Not Done,” New York Times (July 8, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/08/us/edward-blum-affirmative-action-race.html. For a comprehensive history of affirmative action and its origins, see Terry H. Anderson, The Pursuit of Fairness: A History of Affirmative Action (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[101] “Johns Hopkins, 15 Other Universities File Court Document Supporting Diversity in College Admissions,” The Hub (2018), https://hub.jhu.edu/2018/08/09/hopkins-diversity-amicus-brief/.Also see “Brief of amici curiae Brown University, California Institute of Technology, Carnegie Mellon University, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Duke University, Emory University, Johns Hopkins University, Princeton University, University of Chicago, University of Pennsylvania, Vanderbilt University, Washington University in St. Louis, and Yale university in support of respondents.” Nos. 20-1199 & 21-707. Supreme Court of the United States. https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/20/20-1199/232422/20220801150520881_20-1199%20%2021-707%20bsac%20Universities.pdf.

[102] See “Fast Facts,” Office of Undergraduate Admissions, Johns Hopkins University. 2024. https://apply.jhu.edu/fast-facts/.

[103] See the dissenting opinion in the Supreme Court’s decisions, submitted by Sonja Sotomayor and concurred by Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. Also see former First lady Michelle Obama’s response to the decision posted to her social media on June 29, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/michelleobama/p/CuFBNJ1uRb5/?img_index=1.

[104] See the open letter by the JHU Black Student Union posted to Instagram on October 6, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/DAy4oKyhb1V/.

[105] “Interview with President Ronald J. Daniels: Freedom of Expression, Diversity in Admissions, Policing and More,” The Johns-Hopkins News-Letter (2024), https://www.jhunewsletter.com/article/2024/12/interview-with-president-daniels-freedom-of-expression-diversity-in-admissions-policing-and-more. Also see “Johns Hopkins Affirms Commitment to Diversity in Wake of Supreme Court Decision on Race in Admissions,” The Hub (2023), https://hub.jhu.edu/2023/06/29/scotus-affirmative-action-johns-hopkins-message/.

[106] “U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights Sends Letters to 60 Universities Under Investigation for Antisemitic Discrimination and Harassment,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Education (March 10, 2025). https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/us-department-of-educations-office-civil-rights-sends-letters-60-universities-under-investigation-antisemitic-discrimination-and-harassment. “Feds threaten Hopkins, other colleges with funding cuts over antisemitism claims,” Baltimore Banner (March 11, 2025). URL: https://www.thebaltimorebanner.com/education/higher-education/johns-hopkins-palestine-encampment-antisemitism-warning-W23PKIOVBZHXTOLA3D72SKW2YM/. Also see Hirsch, Marianne. “There’s a Bleak Historical Explanation for Why Columbia’s Capitulation to Trump Is So Concerning.” Forward (2025). Published electronically March 23, 2025. https://forward.com/opinion/706984/columbia-university-trump-nazi-germany/.

[107] “Johns Hopkins aid groups to lay off more than 2,000 amid Trump cuts,” Baltimore Banner (March 13, 2025). https://www.thebaltimorebanner.com/community/public-health/johns-hopkins-jhpiego-layoffs-ZPM45MJOFZESXBPZDS6BK4CGM4/. “HHS cuts millions in grants to Hopkins and University of Maryland, Baltimore,” Baltimore Banner (March 25, 2025). https://www.thebaltimorebanner.com/community/public-health/johns-hopkins-maryland-nih-research-NLNPGM76LNBA5JTA3F4XRB3MM4/.

[108] “Visas revoked from 37 Johns Hopkins University students in Maryland, officials say,” WJZ News/ CBS (April 17, 2025). https://www.cbsnews.com/baltimore/news/maryland-international-student-visas-revoked-us-johns-hopkins/. “University addresses visa reinstatements and ICE protocols in second “Community Updates” briefing,” JHU News-Letter (May 2, 2025). https://www.jhunewsletter.com/article/2025/05/university-addresses-visa-reinstatements-and-ice-protocols-in-second-community-updates-briefing.

[109] Note: Johns Hopkins annual budget stands at approx. $6.5 billion, $3 billion of which as spent on research. “Federal cuts have been brutal for Johns Hopkins. Here’s how its endowment can help,” Baltimore Banner (April 30, 2025). “Johns Hopkins Taps Endowment Earnings to Fund Research,” Inside Higher Ed (April 30, 2025). https://www.insidehighered.com/news/quick-takes/2025/04/30/johns-hopkins-taps-endowment-earnings-research-funding.

© 2025. This text is openly licensed via CC-BY. The images are not subject to a CC licence.