Amid rising authoritarianism and mounting challenges for international scholars in the United States, maintaining strong transatlantic academic ties has never been more critical. Reflecting on four weeks as a Visiting Scholar at the University of Kansas in April 2025, Timothy Nunan explores both the vibrant intellectual exchanges still possible and the political turbulence threatening them.How can European universities, particularly German institutions, maintain their longstanding ties with American partners in an era of unprecedented assaults on academic freedom and the physical security of students? Encouraging others follow him on the road to Kansas, he also reflects on the ecosystem, indigenous culture, cuisine and presidency of Harry S. Truman that shapes life on campus and beyond in the US Midwest.

1000 Cranes artwork at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Independence, MO. Photo: Timothy Nunan

Generate PDF

the Trump Administration has also unleashed a war on higher education, including the disappearance of foreign students.

Three months into the second Trump Administration, the United States has become a major source of global instability. Trump’s Vice-President, J.D. Vance, thumbed his nose at European elites during his appearance at the Munich Security Conference on February 14, 2025. Meanwhile, Trump and Vance’s mafia-style shakedown of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on March 1, 2025, provided little reason for hope regarding Trump’s policy toward Russia. A month later, on April 2, 2025, Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs threatened to upend the entire global economy, particularly the US-China economic relationship.

doi number

doi: 10.15457/frictions/0041

How can European universities, particularly German institutions, maintain their longstanding ties with American partners in an era of unprecedented assaults on academic freedom and the physical security of students? More broadly, where is the relationship between America and Europe headed in an era defined by surging right-wing authoritarianism in the former and efforts to uphold a liberal center in the latter?

Throughout this time, the Trump Administration has also unleashed a war on higher education, including the disappearance of foreign students. On March 8, agents from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) abducted Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian student at Columbia, from his apartment and jailed him in a Louisiana prison—all without any criminal charges. After Trump threatened to withdraw $400 million in federal funding from Columbia University, the university administration folded on March 21, 2025, agreeing to new disciplinary procedures and unprecedented surveillance of academic programs focused on the Middle East.

Days after Columbia’s surrender, Tufts University graduate student Rümeysa Öztürk, a Turkish citizen, was kidnapped by plainclothes officers on the streets of Boston and sent, like Khalil, to Louisiana, again without any criminal charges. Khalil and Öztürk’s only “offense,” it appears, was their peaceful opposition to Israel’s ongoing war on Gaza, as Khalil had participated in campus protests and Öztürk had written op-eds for student newspapers.

With stories like these—not to mention several others involving European researchers stopped at the US border due to their criticism of US policy—it is little wonder that many international researchers are reconsidering their planned research stays or vacations to the United States. Scholarly conferences held in the United States are frequent hubs for international scholarship, and with both the football (soccer) World Cup and the Olympics scheduled to take place in the USA during what will almost certainly be a Trump (or Vance) presidency, these concerns are unlikely to dissipate anytime soon.

How can European universities, particularly German institutions, maintain their longstanding ties with American partners in an era of unprecedented assaults on academic freedom and the physical security of students? More broadly, where is the relationship between America and Europe headed in an era defined by surging right-wing authoritarianism in the former and efforts to uphold a liberal center in the latter?

Area Studies on the Prairie

With these questions in mind, I had the privilege of spending three weeks as a Visiting Scholar at the University of Kansas this April 2025, thanks to the support of the Leibniz ScienceCampus “Europe and America in the Modern World.” Located in Lawrence, KS, slightly less than an hour west of Kansas City, Missouri, the University of Kansas was an attractive destination for several reasons.

Timothy Nunan with the KU mascot, Big Jay, or the Jayhawk. Photo: Maxie Schrieber

The University of Kansas (KU) is home to several major area studies centers, focusing on Africa, East Asia, Latin America, and, most relevant for me, a Center for Russian, Eastern European & Eurasian Studies (CREEES). This focus on area studies makes KU a natural counterpart to the focus in Regensburg, including at the LSC and DIMAS, on similar fields. My own scholarly work had brought me into conversation with KU historians like Erik Scott, the director of CREEES, and Sheyda Jahanbani, a scholar of American relations, so I was eager to spend more time exchanging ideas with them. Additionally, I knew one of CREEES’ postdoctoral fellows, Rebecca Johnston, having studied Russian with her many years ago.

Before long, I was on a plane to Kansas City and then to Lawrence, where an intense schedule took shape. Professor Jahanbani invited me to her undergraduate course on the history of globalization, where I delivered a lecture on the history of Islamism during the Cold War, the topic of my recently completed book manuscript. Afterwards, I presented to KU undergraduate and graduate students about the University of Regensburg as a host for international fellowships. US-American students and postdoctoral scholars are often unfamiliar with the organization of German universities and academic institutions like Leibniz Institutes and Max Planck Institutes.

In terms of more formal talks and lectures, the Max Kade Center for German-American Studies kindly invited me to deliver a lecture on the current state of German and trans-Atlantic politics. In the talk, titled “Sick Man of Europe?”, I reflected on how the superficial calm of the Merkel years (2005-2021) masked several growing problems in German society. The “debt brake” led to chronic underinvestment in public infrastructure, while naïveté about Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the American right allowed German elites to avoid making contingency plans for 2022 and, as it turned out, 2024. The talk was well attended by KU German Department faculty like Marike Janzen and Nina Vyatkina, as well as emeritus faculty like Jim Morrison and interested members of the Lawrence community. A dinner invitation from Professor Janzen, together with Professor Vyatkina and Professor Ben Chappell, allowed us to continue the conversation about German-American relations in the era of Trump and Merz.

An Outing to the Harry S. Truman Presidential Museum

Truman faced some of the most consequential decisions in American history: the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the founding of the United Nations, and managing relations with Joseph Stalin. And these were only the first few months!

While talks and engagements with students and faculty formed the core of my stay in Lawrence, I also took time to explore the cultural offerings of Kansas City and the surrounding prairie landscape. Near the end of my second week in Lawrence, Professor Jahanbani graciously invited me to accompany her to Kansas City to visit Arthur Bryant’s BBQ and the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum. Kansas City is renowned throughout the US for its excellent barbecue, and Arthur Bryant’s BBQ is perhaps the most famous of its barbecue restaurants. A hearty meal of “burnt ends” (trimmings from smoked beef brisket) did not disappoint.

Well fed after our stop at Arthur Bryant’s, Professor Jahanbani and I continued to the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Independence, MO, just down the road from Kansas City. We were treated to a tour of the new exhibition by Museum Director Mark Adams. Truman unexpectedly became President just months after being sworn into office when U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945. As the exhibition expertly reminded us, Truman faced some of the most consequential decisions in American history: the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the founding of the United Nations, and managing relations with Joseph Stalin. And these were only the first few months! Later years of Truman’s first term saw momentous events like U.S. recognition of the State of Israel and the Berlin Blockade, while Truman’s second term coincided with the Korean War and the transformation of the Cold War into a global, militarized conflict.

The exhibition offered a glimpse into the state-of-the-art practices of historical museums in the USA. Adams and his team expertly used primary source documents alongside films to do justice to such complex episodes. The tour proved enormously instructive, especially since I teach a lecture course on the history of the Cold War and often struggle to convey to students the sheer density and magnitude of the decisions Truman had to make. Particularly striking was a letter from U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson to Truman on April 24, 1945, demanding an urgent meeting with the new President to inform him about the existence of the atomic bomb program. Truman had not been informed about the atomic bomb program while serving as Senator from 1935-1946, and he had only been added to the 1944 presidential ticket as a compromise between factions in the Democratic Party.

The museum also took care not to narrate history solely through the perspective of US power. In the exhibition room devoted to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, for instance, the exhibit touched on the story of Sadako Sasaki, a Japanese girl who survived the bombing of Hiroshima. Not long after the destruction of Hiroshima, Sasaki developed leukemia with slim chances of survival. As Sasaki struggled with cancer in a hospital, she folded over 1,000 miniature origami cranes. According to Japanese folklore, cranes can live 1,000 years; those who fold an origami crane for each year of a crane’s life will be granted a wish. Sasaki’s folding of the origami cranes did not slow the leukemia, and she passed away at age 10. The museum highlighted one of Sasaki’s origami cranes across from the bomb plug for one of the atomic bombs, underscoring the horrible tension between Truman’s wish to end World War II and the enormous number of innocents killed in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. During the pandemic, Adams added, the Museum encouraged students at Kansas City schools to fold their own origami cranes to honor Sasaki’s memory.

Particularly interesting was how the museum, using Truman’s extensive, decades-long correspondence with his wife Bess, did not shy away from underscoring Truman’s openly racist attitudes as a young man. Over time, Truman evolved on questions of race, integrating the US federal government and the army. Precisely when and how Truman shifted his views is difficult to say. But, according to Adams, Truman’s experience serving in World War I as a soldier and subsequently seeing the mistreatment of African-American veterans of World War II after 1945 likely played a role. Truman appears to have been particularly shaken by the February 12, 1946, maiming of Isaac Woodard, an African-American veteran who was attacked and blinded while still wearing his uniform by policemen in Batesburg, South Carolina. Portions of the exhibition devoted to Sasaki and Woodard did justice to groups whose stories have too often been marginalized in histories of the United States.

Of Powwows and Bison

it’s easy to forget that the underlying prairie (i.e., steppe) constitutes its own distinctive ecosystem. Many indigenous species of flora and fauna were displaced by the introduction of European species and the arrival of settlers.

After the journey to Kansas City, I maintained an energetic schedule by attending events and visiting sites that are truly distinctive to Kansas and its prairie ecosystem. My visit to Lawrence coincided with the annual KU Powwow and Indigenous Cultures Festival, an event that celebrates and honors indigenous peoples around the KU community. As the event’s website reminds us, powwows “are Tribal celebrations of community and spirituality steeped in tradition and protocol. It is a cultural celebration to which you have been invited, and the Tribal protocols used were founded and used for thousands of years to carry on the way of life for Tribal peoples.”

At the powwow, I observed several distinctive dances and dress of the Indigenous peoples of the territories that today comprise Kansas, while Indigenous drummers provided the musical backdrop to the native dance. Videos of some of the dances can be found via the YouTube channel of the Haskell Indian Leader, the student newspaper of the Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence.

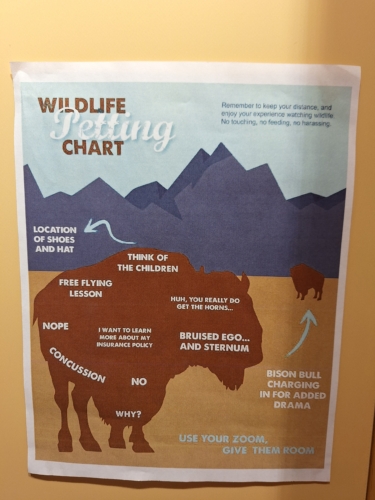

Beyond the KU Powwow, I took advantage of the car I had rented and ventured out into the real prairie, specifically the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve. Given that Kansas’s economy is dominated by agriculture, it’s easy to forget that the underlying prairie (i.e., steppe) constitutes its own distinctive ecosystem. Many indigenous species of flora and fauna were displaced by the introduction of European species and the arrival of settlers. Perhaps the most tragic case was that of the American bison, which once numbered in the tens of millions but was nearly wiped out following European settlement and the destruction of Indigenous tribes. Fortunately, conservation efforts have stabilized the bison population, and they now live in the wild in many parts of North America.

The Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve aims to preserve both the prairie ecosystem and the American bison. Spanning approximately 44 square kilometers, about two hours west of Lawrence, the preserve allows guests to walk through protected prairie landscapes and enter fenced pastures home to around 100 American bison. Observing these majestic creatures, which can weigh over 1,000 kilograms, was an amazing experience—best enjoyed at a distance, as bison can charge if they feel provoked. A helpful poster at the Visitor Center reminded me of the risks of getting too close to bison.

Information Panel at the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve. Photo: Timothy Nunan

Hiking through the bison pasture required careful triangulation to maintain the requisite 100 meters distance from them. A moving bison herd eventually forced me to turn around and take an alternate route back. Nonetheless, this visit to the sweeping prairie landscape and encounter with some of its oldest inhabitants offered a reminder of the diversity of the American continent and the impacts of European colonialism.

On the prairie. Photo: Timothy Nunan

Back to Lawrence

My final week in Lawrence saw me returning to the lecture podium and classroom, while also taking time to meet KU faculty and remind them of the Leibniz ScienceCampus’ incoming fellowships. Having recently received a major AHRC-DFG grant for a project on the history of sexualities in the Soviet Union and its successor states (particularly Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan), I shared an early overview of this research agenda with an audience at CREEES. Later that week, my colleague and friend Dr. Rebecca Johnston invited me to her Soviet history seminar, where I gave a guest lecture on the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the topic of my first book.

In between these formal events, I enjoyed meeting with KU officials like Charles Barker (Senior Internationalization Officer) and Joe Potts (Associate Vice Provost for Strategic Partnership and Innovation), who work on university internationalization. As the Internationalization Officer for UR’s Faculty of Philosophy, Art History, History, and Humanities, I discussed possible forms of collaboration between the two universities. More informal meetings with colleagues like Vitaly Chernetsky (Slavic Languages and Literature) and Marta Vicente (History) allowed me to explore potential collaboration ideas related to Eastern European cultural studies and gender and sexuality studies. Professor Chernetsky, a native of Regensburg’s sister city Odesa, has already worked closely with the Denkraum Ukraine, while Professor Vicente’s research in transgender studies makes her a natural interlocutor for UR projects like “Transitions” as well as the Freigeist group “Light On!” and the Zusatzstudium Genderkompetenz.

Mending the Relationship?

It would be naïve to overlook the fundamental changes occurring, given the Trump Administration’s mistreatment of graduate students like Khalil and Öztürk and numerous instances of random arrests of Germans and other Europeans traveling to the USA for conferences or pleasure.

To conclude, where exactly are American universities headed in the age of Trump 2.0? What opportunities and challenges await German universities and institutions like iOS seeking to maintain those trans-Atlantic ties?

It would be naïve to overlook the fundamental changes occurring, given the Trump Administration’s mistreatment of graduate students like Khalil and Öztürk and numerous instances of random arrests of Germans and other Europeans traveling to the USA for conferences or pleasure. In March 2025, German travel to the United States was down by a whopping 28% compared to a year ago. Given that American universities derive a significant portion of their income from international student fees, and that academic excellence anywhere is predicated on securing the best minds regardless of their skin color, nationality, or creed, these are worrying trends. As fewer Germans travel to the USA, academic ties are bound to suffer. This will make not only the United States but also Germany more intellectually impoverished. For me, as an American and Fulbright alumnus teaching in Germany, it pains me to see these networks fraying.

Nonetheless, it is precisely to navigate such headwinds that institutions like the Leibniz ScienceCampus “Europe and America in the Modern World” exist. While the Trump Administration and DOGE continue to undermine programs like Fulbright, my trip to Lawrence allowed me to promote German initiatives like the DAAD and the Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship, which still bring talented Americans to German universities. Likewise, European funding programs like the European Research Council can bring American researchers to German institutions of higher education, and programs like Horizon Europe can involve American partner institutions. Granted, German and European initiatives cannot replace American research funding. But as Trump 2.0 puts trans-Atlantic ties under the greatest stress in living memory, maintaining trans-Atlantic ties through academia is more important than ever.

© 2025. This text is openly licensed via CC-BY. Separate copyright details are provided with each image. The images are not subject to a CC licence.